You’ve seen rockets land like slow-motion miracles, but you probably wonder how that works in plain physics. Reusable rockets save money and reduce space debris by bringing the most expensive parts back to Earth using controlled burns, aerodynamic steering, and precision landings. This article will break down the core forces, fuel trades, and engineering tricks that let boosters survive launch, return through hypersonic heating, and touch down upright.

You’ll follow simple explanations of thrust, staging, and re-entry physics, then watch those basics connect to the practical steps—boostback burns, grid-fins steering, and landing burns—that make reuse possible. Expect clear examples of current technology, the companies pushing the field forward, and why reusability changes the economics and environmental footprint of space travel.

The Fundamentals of Rocket Physics

Rockets convert stored chemical energy into directed exhaust momentum to change velocity, overcome gravity, and steer during ascent and recovery. You’ll focus on how forces, mass change, and engine performance set the limits for reusable flight.

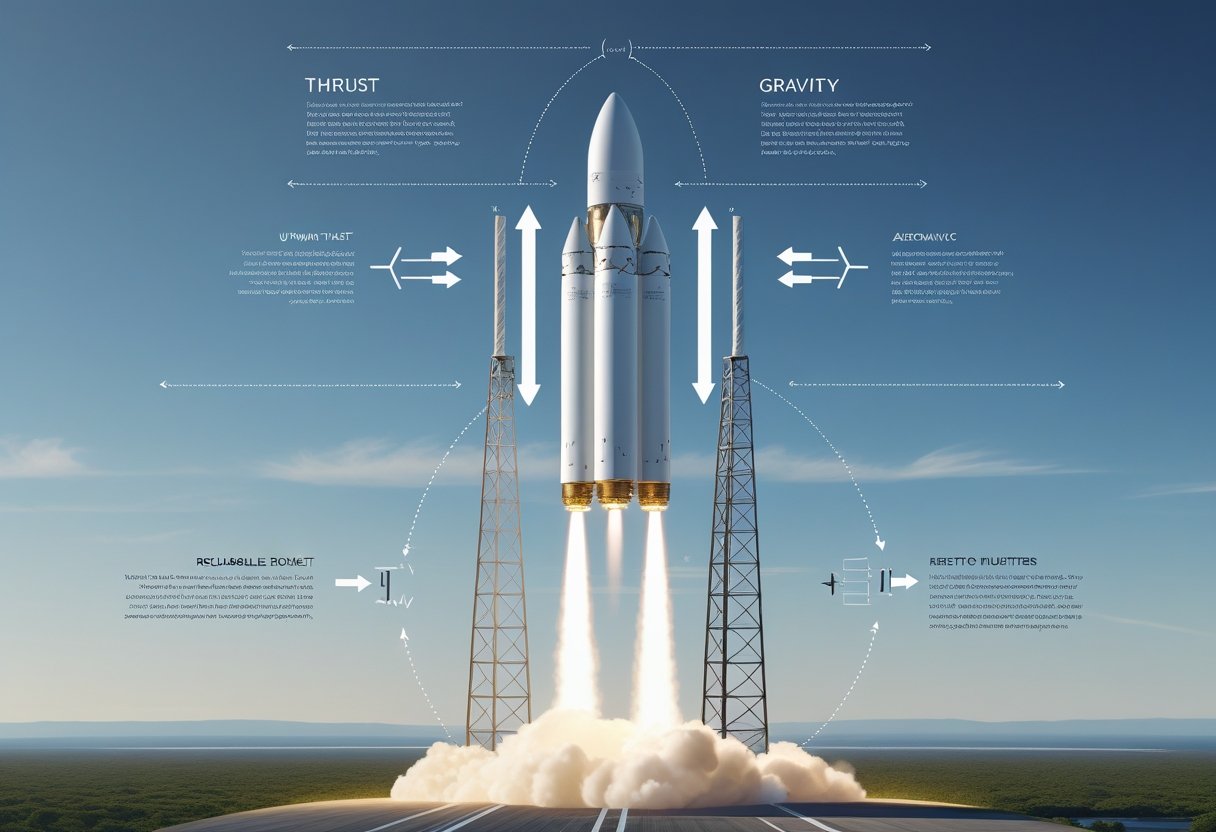

Newton’s Laws of Motion in Rocketry

You apply Newton’s laws to predict acceleration and control. First, inertia means your rocket resists changes in motion; heavy payloads and fuel mass make initial acceleration small. Second, F = ma ties thrust, vehicle mass, and acceleration: as you burn propellant, mass drops and the same thrust produces larger acceleration. Third, every force has an equal and opposite reaction; thrust arises because exhaust gases push backward while the rocket moves forward.

Gravity acts constantly downward, so your net upward acceleration equals (thrust − weight)/mass. During landing burns you manage small net thrust close to weight to decelerate without stalling control. Understanding these laws helps you size tanks, choose staging, and program guidance to meet performance and reusability goals.

Principle of Action and Reaction

Action and reaction explain thrust in the clearest terms: eject mass rearward and the rocket gains forward momentum. You measure performance by specific impulse (Isp), which equals effective exhaust velocity divided by g0; higher Isp means more delta-v per kilogram of propellant. The classical rocket equation Δv = ve ln(m0/mf) shows how exhaust velocity (ve) and mass ratio determine your achievable velocity change.

Exhaust speed and mass flow are determined at the engine nozzle and combustion chamber. For reusable rockets you balance high ve (efficient propellants) with restartability and throttling for controlled landings. Engines like SpaceX’s Merlin trade slightly lower Isp for robust reusability and good throttle response, letting you perform boostback and landing burns reliably.

Role of Propellant and Rocket Engines

Propellant choice and engine design set thrust curve, throttling range, and reusability margins. You pick propellant based on density, performance, storability, and thermal properties. Liquid oxygen (LOX) with RP-1 or liquid hydrogen gives different Isp and density trade-offs; LOX/RP-1 offers dense fuel that simplifies tanks and reutilization cycles, while LOX/LH2 yields higher Isp but heavier insulation and larger tanks.

Rocket engines convert chemical energy into high-speed exhaust via combustion, turbines, pumps, and a nozzle. Key factors you watch: chamber pressure (affects thrust and efficiency), nozzle expansion ratio (matches exhaust to ambient pressure), and turbopump reliability (critical for repeated flights). For reusable stages you need engines designed for repeated thermal cycles, with materials and cooling that tolerate high chamber temperatures and thermal shock. Engines such as the Merlin exemplify this approach: relatively simple cycle, deep throttling, and refurbishment-friendly components that support frequent reuse.

What Makes Rockets Reusable?

You’ll learn how reusable rockets recover valuable hardware, how they differ from single-use designs, and which parts engineers focus on to cut cost and turnaround time.

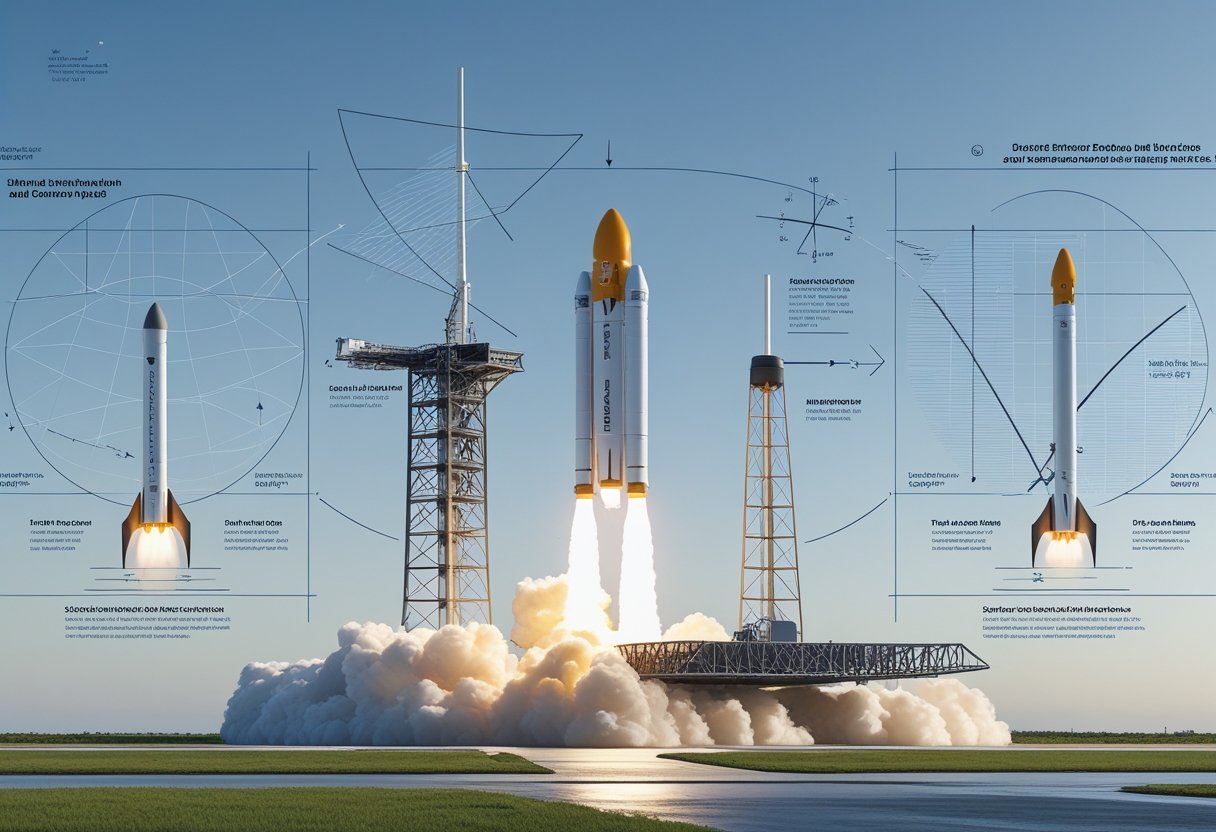

Definition of Reusable Rockets

A reusable rocket, or reusable launch vehicle, deliberately recovers and flies one or more major components after a mission so you don’t discard them. Most programs reuse the first stage booster because it contains the largest fraction of mass and cost. Reuse can be partial (only first stage) or more extensive (boosters, fairings, or even second stages and spacecraft).

Reusability reduces marginal cost per flight by spreading production and refurbishment costs across multiple launches. You’ll judge reusability by refurbishment costs, turnaround time, and demonstrated flight life of components. Companies measure cycles per booster and parts replaced per cycle to calculate savings versus expendable rockets.

Common recovery methods include propulsive vertical landings on ground or droneship, controlled ocean splashdowns for retrieval, and capture of payload fairings. Your program’s choice affects inspection needs, corrosion risk, and refurbishment complexity.

Contrast with Expendable Rockets

Expendable rockets are single-use: you discard stages after they complete their mission. That design minimizes recovery hardware mass and simplifies structural margins, but it forces you to build new stages for each flight, raising cost per launch.

Expendable stages avoid landing systems, heat-shielding for reentry, and heavy landing legs or grid fins. You’ll notice simpler certification and fewer inspections, but higher raw-material and manufacturing expenses. For high-volume launch markets, expendable economics can’t match reusability unless manufacturing is extremely cheap.

Operationally, expendable rockets typically have faster individual launches because they skip recovery operations. However, if you launch frequently, reusable rockets lower average cost and enable rapid cadence once refurbishment processes mature.

Key Components Designed for Reuse

Engineered-for-reuse components include the first-stage booster, payload fairings, and increasingly second stages or spaceplanes. The booster combines structural hardening, thermal protection for reentry, and flight-control surfaces like grid fins to steer during descent.

Propulsion recovery relies on restartable engines and multiple burns: boostback, reentry, and landing burns. You’ll need durable turbopump and chamber materials, plus sensors and avionics rated for multiple thermal cycles. Landing hardware—legs, actuators, and sensors—must survive impact loads and be quickly inspected.

Refurbishment costs hinge on accessible designs, modular replaceable parts, and minimized post-flight inspections. For example, fairing recovery systems (parachutes, parafoils, or ship-capture nets) aim to reduce saltwater exposure and cleaning time. Tracking refurbishment metrics—man-hours per stage, parts replaced, and mean flights between overhauls—lets you quantify whether reusability yields real savings over expendable rockets.

For an overview of reusable system design strategies and European heritage, see this review of reusable space systems and technology aspects (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094576521003970).

How Reusable Rockets Work: Step-by-Step

You’ll follow a precise, fuel-managed sequence that returns the most expensive part—the first stage booster—back to a chosen landing site. Key actions include engine reignitions, aerodynamic control with grid fins, and timed burns that change trajectory for a vertical landing.

Launch and Stage Separation

You feel the rocket’s thrust during liftoff as nine Merlin engines push the vehicle through dense atmosphere. The first stage carries the rocket until main-engine cutoff (MECO), then stage separation separates the booster from the second stage and payload with pyrotechnic or mechanical actuators.

After separation, the second stage continues to orbit while the first stage begins orientation and attitude control. Your booster uses cold gas thrusters and reaction control systems to stabilize and point its engines for the next maneuver. Accurate timing at separation minimizes wasted propellant and sets the booster on the precise return profile you planned.

The Flip and Boostback Burn

Once clear, your booster flips tail-first using cold gas thrusters and then relights some Merlin engines for the boostback burn. That burn reduces horizontal velocity and shifts the booster’s trajectory toward a designated landing zone—either a shore-based landing pad or an autonomous spaceport drone ship (ASDS) at sea.

You manage fuel reserves tightly during boostback. The magnitude of the burn depends on payload mass and target: heavy payloads often require a droneship landing downrange, while lighter missions allow a boostback to the launch site (RTLS). This step determines whether the booster will perform a long reentry or a shorter return to the launch zone.

Atmospheric Reentry and Steering

As your booster re-enters at hypersonic speeds, it faces intense heating and aerodynamic forces. You deploy and control large grid fins to steer through the plasma-tinged wake, making small, rapid inputs to guide the vehicle toward the landing target.

You also perform a reentry burn using a subset of engines to slow and protect the structure. That burn reduces both thermal and mechanical loads. During this phase, telemetry and inertial navigation maintain the flight solution, while the grid fins and cold gas thrusters trim attitude for the final landing approach.

Controlled Landing and Recovery

In the final phase, you perform a landing burn with a single engine to bleed off vertical velocity for a soft touchdown. Landing legs deploy in the last seconds to absorb touchdown loads and stabilize the booster in a vertical landing posture.

If you aim for the ASDS, precision guidance aligns the booster with the ship’s deck. For return-to-launch-site landings, the boostback profile and guidance center the booster on the landing zone. After touchdown, recovery crews secure the booster; refurbishment crews then inspect the first stage booster for reuse, turning the recovered hardware into a reflown vehicle with reduced cost per launch.

Pioneers and Modern Technologies in Reusable Rockets

Reusable rockets evolved from partial component recovery to near-full-stage reusability, driven by engineering tradeoffs, cost aims, and new materials. You will see how the Space Shuttle’s mixed approach informed later designs, how SpaceX transformed first-stage reuse with Falcon 9 and pushed toward Starship/Super Heavy, and how competitors use different technical paths like vertical landing, parachutes, and stage refurbishment.

The Space Shuttle Era

The Space Shuttle introduced large-scale reuse with a winged Orbiter and recoverable Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs). You should note the Shuttle reused RS-25 engines and the Orbiter for many missions, but discarded the External Tank each flight, showing early tradeoffs between mass, complexity, and turnaround time.

Recovering SRBs required ocean retrieval, refurbishment, and requalification, which proved costly and labor-intensive. The Shuttle’s thermal protection tiles also demanded extensive inspection after reentry, increasing refurbishment time.

These practical limits taught later designers to favor simpler, robust components that enable rapid reflight. The Shuttle’s operational history still informs modern systems and contrasts with expendable giants like the Saturn V that prioritized payload over reusability.

Rise of SpaceX and Falcon 9

SpaceX proved routine first-stage recovery with Falcon 9 boosters using grid fins, center engine relight, and controlled propulsive landings. You can track Falcon 9’s shift from expendable flights to repeated reuse—boosters now fly a dozen-plus times—cutting launch cost per flight.

Elon Musk’s team prioritized modular refurbishment, telemetry-driven inspections, and autonomous droneship recovery to scale cadence. SpaceX then scaled the approach: Falcon Heavy reuses three cores, and Starship with Super Heavy aims for full stage and upper-stage reusability via rapid propulsive return and tower capture.

This path emphasizes rapid turnaround, minimizing refurbishment, and designing engines (Merlin, Raptor) for many cycles rather than single-use performance.

Competing Innovations: Blue Origin, Rocket Lab, and More

Blue Origin pursued a gentler recovery with New Shepard using parachute and vertical landings for a suborbital vehicle, then scaled to New Glenn’s reusable first stage for orbital lifts. You should watch New Glenn for competition in heavy-lift reuse and Blue Origin’s focus on engine and stage robustness.

Rocket Lab’s Neutron targets medium-lift reusability through controlled stage recovery and refurbishment, differing from its Electron program that used parachute recovery attempts. Other players explore alternate paths: ULA’s Vulcan Centaur plans partial reusability concepts; historical efforts like Buran showed winged automatic return; and companies investigate reusable upper stages, heat-shield tech, or reusable engines.

These varied approaches—vertical propulsive recovery, parachutes, partial component reuse—reflect tradeoffs among complexity, mass penalty, and operating cost, giving you multiple technical templates for future reusable architectures.

Economic and Environmental Impacts

Reusable rockets change how you think about money and the planet. They lower the price of reaching orbit, raise how often rockets fly, and shift spending from manufacturing to inspection and refurbishment.

Slashing Launch Costs

You see biggest savings in the reduced need to build a new first stage for every mission. Reusability cuts the major hardware cost component—boosters and engines—so the cost per launch can fall by tens of percent compared with fully expendable vehicles. That translates into cheaper satellite rides and lower barriers for startups and universities to buy launches.

Be mindful that savings depend on turnaround time and refurbishment costs. If refurbishment is fast and inexpensive, per-launch savings stack up. If inspections, part replacements, or engine overhauls remain costly, your total lifecycle cost still includes significant recurring spending.

Operational changes also shift capital: you spend more on recovery infrastructure, specialized landing hardware, and testing facilities. Those are one-time or infrequent investments that can pay off if you increase launch frequency.

Increasing Launch Frequency

You benefit from higher launch cadence when rockets are rapidly reusable. Faster turnaround time—measured in days to weeks rather than months—lets operators fly more missions per vehicle per year. Higher flight rates dilute fixed costs across many launches, lowering average-cost-per-launch even further.

Greater frequency supports commercial spaceflight markets: satellite constellations, on-demand cargo, and space tourism scale faster when launch slots and vehicles are plentiful. That growth changes industry economics, creating new revenue streams for launch providers and downstream services.

Higher cadence also raises logistical and supply-chain demands. You need spares, skilled technicians, and streamlined test procedures to sustain frequent flights without ballooning refurbishment costs. Managing that operational tempo determines whether launch frequency truly reduces your unit costs.

Safety and Refurbishment Considerations

You must balance speed with safety. Each reuse cycle adds wear: thermal stress, structural fatigue, and engine erosion accumulate. Detailed inspections and non-destructive testing become routine costs that protect flight safety. Skipping thorough refurbishment risks failures that could erase economic gains.

Refurbishment costs vary widely by design and propellant choice. Cleaner-burning engines or designs that avoid hot-stage reentry can reduce part replacement frequency, lowering lifecycle expense. Track record matters: documented multiple-flight engines let you predict maintenance intervals and budget accordingly.

Regulatory oversight also affects your timeline and cost. Certification, launch licensing, and demonstrated reliability add upfront expense and can slow turnaround time, but they also reduce operational risk for commercial spaceflight customers and insurers.

The Future of Reusable Rockets and Space Exploration

You will see faster launch cadence, lower marginal costs per payload, and clearer pathways to missions beyond Earth orbit as reusable hardware and operations improve. Advances will affect satellite constellations, commercial travel, and the engineering choices for interplanetary systems.

Next-Generation Vehicles and Interplanetary Missions

You should expect vehicles that go beyond single-use first stages to include large, fully reusable systems like Starship-class ships aimed at delivering cargo and crew to the Moon and Mars. Reusable first stages will continue cutting launch costs for Earth-to-orbit logistics, while larger second-stage reuse or fully reusable two-stage-to-orbit designs will enable more mass to reach escape velocity for interplanetary missions.

Key technical focuses will be heat-tolerant materials, rapid refurbishment processes, and in-space refueling to enable true interplanetary travel. That refueling reduces the mass you must lift from Earth and makes crewed Mars missions and sustained cargo runs feasible. You will see architecture choices shift toward reusable launchers paired with orbital propellant depots and cryogenic transfer techniques to reach Mars efficiently.

Space Tourism and Commercial Opportunities

You can expect suborbital vehicles to mature into routine, short-duration experiences and orbital tourism to expand as reusable systems lower ticket prices. Companies operating vertical-landing suborbital rockets will offer frequent flights for research and private passengers, while larger orbital vehicles and spaceplanes aim to carry paying customers to destinations such as low Earth orbit hotels or short stays at private stations.

Commercial opportunities will grow in satellite servicing, on-orbit manufacturing, and point-to-point high-speed travel. Reusable first stages and rapid turnaround will make constellation maintenance—like expanding or replenishing Starlink-style networks—cheaper and faster. You will also see new business models: fractional ownership of flight hardware, subscription launches for constellations, and bundled logistics for lunar and cis-lunar commerce.

Toward Sustainable Space Exploration

You will need sustainable practices to scale human activity in space without unsustainable waste or prohibitive cost. Reusing first stages and designing for quick refurbishment reduces manufacturing demand and lifecycle emissions compared with expendable rockets. Emerging practices will include standardized, modular components that you can swap and recycle between missions.

Sustainability will also rely on in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) at the Moon and Mars to produce propellant and materials, minimizing the mass you must launch from Earth. Single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) concepts and spaceplanes will be revisited where they offer operational simplicity, but practical near-term gains will likely come from incremental reuse and refueling infrastructure. You should expect environmental metrics and life-cycle accounting to become routine parts of mission planning.

Leave a Reply