You face extremes in space that would destroy ordinary machines: blistering heat near re‑entry or the Sun, and deep cold in shadowed regions or during lunar nights. Spacecraft survive these extremes by combining insulation, reflective coatings, regulated heaters, radiators, and fault‑tolerant electronics so systems stay within safe temperature limits.

As you explore how engineers manage thermal risks, you’ll learn why vacuum, radiation, and micrometeoroids matter, and how passive methods like multilayer insulation and surface finishes work alongside active systems such as fluid radiators and heaters.

You’ll also discover recent innovations and the special tricks used for deadly situations—re‑entry heat shields and survival through lunar nights—so you can appreciate both the elegant simplicity and the high‑risk engineering behind every mission.

The Space Environment: Understanding Temperature Extremes

Space exposes your spacecraft to wide temperature swings driven by radiation, lack of air, and local surface properties. You must manage direct sunlight, reflected light, and the way materials emit and absorb heat.

Vacuum and Heat Transfer in Space

In vacuum, conduction and convection are negligible, so radiation becomes the dominant heat-transfer mechanism. Your spacecraft exchanges energy by emitting infrared photons according to surface temperature and emissivity; low-emissivity surfaces hold heat longer, while high-emissivity coatings radiate it away faster.

Internal conduction still moves heat between components through structural paths, so thermal coupling and isolation matter. Designers use heat pipes and conductive straps to move heat from hot electronics to radiators. Multi-layer insulation (MLI) reduces radiative exchange between spacecraft and space, lowering heat losses or gains depending on mission phase.

You must also consider transient events: eclipse entries cut solar input in seconds, causing rapid cooling, while thruster firings or instrument operations create localized heating that conduction must spread to avoid hotspots.

Solar Radiation and Albedo Effects

Solar irradiance at Earth distance is about 1,360 W/m², and direct sunlight can rapidly heat sun-facing surfaces. Your thermal design must handle this steady flux as well as spikes from solar flares that increase particle radiation and can alter surface heating indirectly.

Albedo—the fraction of sunlight reflected by a planet or surface—adds a variable reflected load. Over the Moon, highland regolith can increase reflected visible light and heat; around Earth, cloud cover and ice fields change albedo significantly and repeatedly. Optical properties matter: surface absorptivity in visible wavelengths and emissivity in infrared determine net heat gain.

You should select coatings and finishes to tune absorptivity/emissivity ratios. For example, white paints lower solar absorption; polished metals reflect sunlight but may also lower infrared emissivity, complicating radiator performance. Predictive thermal models include solar geometry, albedo maps, and surface optical constants to estimate heating accurately.

Thermal Environments in Orbit and on Planetary Surfaces

Low Earth Orbit gives you alternating hot/cold cycles roughly every 45–90 minutes depending on altitude and inclination. Day-night cycles drive temperature swings; trapped radiation belts add particle flux that can cause secondary heating and degrade materials over time. You must model orbital parameters and include thermal control for continuous electronics operation.

On the lunar surface or Mercury, you face extreme static conditions: long sunlight periods produce temperatures above 100°C on sunlit surfaces, while long nights plunge to −150°C or lower. Lack of atmosphere means no convective moderation. Planetary atmospheres change the picture—Venus’s dense atmosphere produces high convective and conductive heating with surface temperatures above 460°C, requiring special thermal protection.

Design choices differ by environment: radiators and louvers work well in vacuum and moderate orbits; active cooling and high-temperature materials become necessary near the Sun or on hot planetary surfaces. You must also account for space radiation and cosmic rays, which can affect optical properties and heat-transport mechanisms over mission lifetimes.

Thermal Risks and Challenges for Spacecraft

You need systems that balance rapid heating, deep cold, and energetic radiation while protecting structure, electronics, and mission-critical sensors. Below are the specific dangers, how they arise, and which spacecraft elements you must protect.

Hot and Cold Hazards

Direct solar heating can drive surface temperatures above 150°C on sun-facing components, while shaded areas can fall below -150°C. You must prevent thermal expansion and contraction that warps instrument alignment, seals, and mechanical interfaces. Use of high-emissivity coatings and deployable radiators helps reject absorbed heat, and thermal isolators or flexible mounts reduce stress where different materials meet.

Cold risks focus on material brittleness and lubricant freezing. Batteries and propellant lines require electric heaters or low-temperature thermostatic control so you don’t lose power or fuel flow. For payloads, temperature gradients as small as a few degrees can change optical path lengths; you must maintain stability using insulation, thermal straps, and phase-change materials that buffer transients.

Spacecraft Temperature Fluctuations

Your spacecraft often cycles between sunlight and shadow every orbit, producing repeated thermal swings. Those cycles cause fatigue in brackets, welds, and connectors; design-level thermal cycling tests simulate thousands of transitions to qualify components. Small satellites face larger swings because their small thermal mass heats and cools quickly, so radiator sizing and MLI layout become critical design choices.

Internal heat sources—processors, radios, and reaction wheels—create localized hot spots. You must route heat via heat pipes or looped fluid systems to radiators and avoid hot junctions near sensitive electronics. Thermal modeling using orbital parameters and material properties helps predict steady-state and transient temperatures before you build hardware.

Radiation-Induced Threats

Ionizing radiation does more than damage electronics; it alters material properties over time. You need to account for cumulative dose causing embrittlement in polymers, discoloration of thermal coatings, and changes in emissivity that reduce radiator effectiveness. Select radiation-tolerant materials and test coatings for long-duration exposure to vacuum ultraviolet and charged particles.

Energetic events like solar particle events can deposit heat and charge on external surfaces, producing arcing or localized heating. You must provide conductive paths for charge dissipation and verify thermal coatings do not trap charge. Combine radiation-hard electronics, shielding where mass permits, and periodic thermal recalibration of sensors to preserve both structural integrity and measurement accuracy.

Principles of Spacecraft Thermal Control

You’ll learn how heat moves through a spacecraft, how engineers predict temperature behavior, and how thermal measures tie directly into structural, power, and payload choices. Expect concrete tactics you can apply when assessing or designing a thermal control system (TCS).

Fundamentals of Heat Transfer

You must manage three heat paths: radiation, conduction, and (internally) negligible convection. In vacuum, radiation dominates—you control it with surface coatings, optical properties, and radiator area. Emissivity and absorptivity numbers determine how much solar and internal heat a surface emits or absorbs; pick coatings to match mission orbit and attitude.

Conduction moves heat through structural members and harnesses. You’ll use thermal straps, heat pipes, and conductive mounts to move heat from hot electronics to radiators. Design for low thermal resistance where you need heat transport, and high resistance where you want isolation.

Internal heat generation from processors, batteries, and heaters requires distribution and dump capability. Balance passive elements—MLI blankets, surface finishes—with active devices—heaters, loop heat pipes, and pumped fluid loops—so components stay inside operational temperature ranges.

Thermal Analysis and Simulation

You’ll create a thermal model early and update it iteratively. Start with component-level steady-state calculations, then build a spacecraft-level nodal network for transient and orbital variation analysis. Use view-factor radiation calculations and finite-difference or finite-element conduction meshes to capture hot spots.

Run orbital scenarios: worst-case hot (full solar exposure), worst-case cold (eclipse, deep-space view), and transient events like attitude maneuvers. Validate models with thermal vacuum tests and instrument-level thermal balance tests. Capture uncertainties by applying sensitivity analyses and margins for heater power, surface property degradation, and variable internal dissipation.

Document assumptions: material thermal properties, interface conductance, and predicted degradation of coatings. That clarity lets you justify radiator sizing, heater placement, and contingency margins in the TCS.

Integration With Spacecraft Design

Thermal design cannot be isolated; you must trade among mass, power, and mechanical layout. Place high-dissipation units near dedicated radiators or structural paths to minimize heavy heat pipes. Co-locate thermally compatible subsystems to simplify isothermal zones and reduce harness complexity.

Allocate radiator area against available attitude and sunshade geometry. Coordinate with avionics, structures, and power teams so radiator orientation, multi-layer insulation (MLI) coverage, and mounting points align with deployment and launch constraints. Define thermal interface control documents (ICDs) to lock down allowed conductances and heater control strategies.

Plan for growth and unknowns by reserving margin in heater power and mounting provisions for additional thermal straps. You’ll ensure the TCS meets operational limits throughout mission life by making thermal requirements part of every design review and test milestone.

Passive Thermal Control Techniques

Passive thermal control keeps components within safe temperatures using materials and geometry rather than power or moving parts. You’ll rely on reflective coatings, layered insulation, and structural sunshields to limit heat gain, retain heat where needed, and reduce thermal gradients across your spacecraft.

Multi-Layer Insulation (MLI) and Blankets

MLI blankets use alternating layers of low‑emissivity films and spacers to reduce radiative heat transfer. You’ll commonly see Kapton film or aluminized Mylar as the reflective layers; each layer lowers net emissivity so a stack of 10–20 layers can cut radiative exchange by orders of magnitude. Spacers (Dacron netting, for example) prevent conduction between layers.

Design choices matter: layer count, surface finish, and seam treatments determine performance. You must pay attention to seams and penetrations because wiring, fasteners, and deployable joints create thermal shorts. MLI also affects mass and stowage volume; thinner blankets save weight but reduce margin. For long missions, pick materials with verified radiation and atomic oxygen resistance to limit degradation.

Coatings and Optical Properties

Coatings control solar absorptivity (α) and infrared emissivity (ε). You select high‑reflectance, low‑absorptivity coatings (low α) for sun‑facing surfaces to reduce solar heating, and high‑emissivity finishes for radiators to boost heat rejection. Common options include white paints, vapor‑deposited aluminum on Kapton, and specialized thermal control coatings tested for UV and atomic oxygen exposure.

Measure or specify α and ε values; small changes change equilibrium temperatures significantly. Apply coatings consistently and test for adhesion after vibration and thermal cycling. Use different coatings on adjacent surfaces to create thermal balance — for instance, a spacecraft panel may have low‑α on the sunward side and high‑ε on the radiator side. Consider contamination sensitivity; even thin deposits from outgassing will raise α and reduce performance.

Thermal Insulation Materials

Thermal fillers and doublers complement MLI by stopping conduction and evening out temperature gradients. You’ll use foams, aerogels, and honeycomb fillers inside compartments to reduce solid conduction paths. Kapton films function both as structural layers in MLI and as thin dielectric thermal barriers where space and mass are limited.

Select materials based on thermal conductivity, mass, and stability. Aerogel offers very low conductivity but can be fragile; silicone‑based fillers resist vibration but may outgas. Thermal doublers — thin conductive plates bonded across fastener interfaces — spread localized heat from hot spots and prevent cold spots. Validate material choices with thermal vacuum testing and radiation exposure data to ensure long‑term performance.

Sunshields and Louvers

Sunshields and deployable sunshades block direct solar flux and reduce view factors to hot bodies. You’ll often see multi‑layer sunshields (Kapton or aluminized films) on missions like inner‑planet probes and telescopes to cut solar input before it reaches sensitive components. Proper deployment sequence and tensioning prevent flutter and preserve optical properties.

Louvers provide passive variable rejection: they expose high‑emissivity surfaces when temperatures rise and close to reduce emission when cold. You choose bimetallic or thermally actuated louvers depending on reliability needs; they require no power but must survive cycling. Place louvers on radiators with controlled view to deep space, and avoid shadowing sensors. Both sunshields and louvers demand careful thermal modeling and mechanical testing to ensure predictable, repeatable behavior.

Active Thermal Control Systems

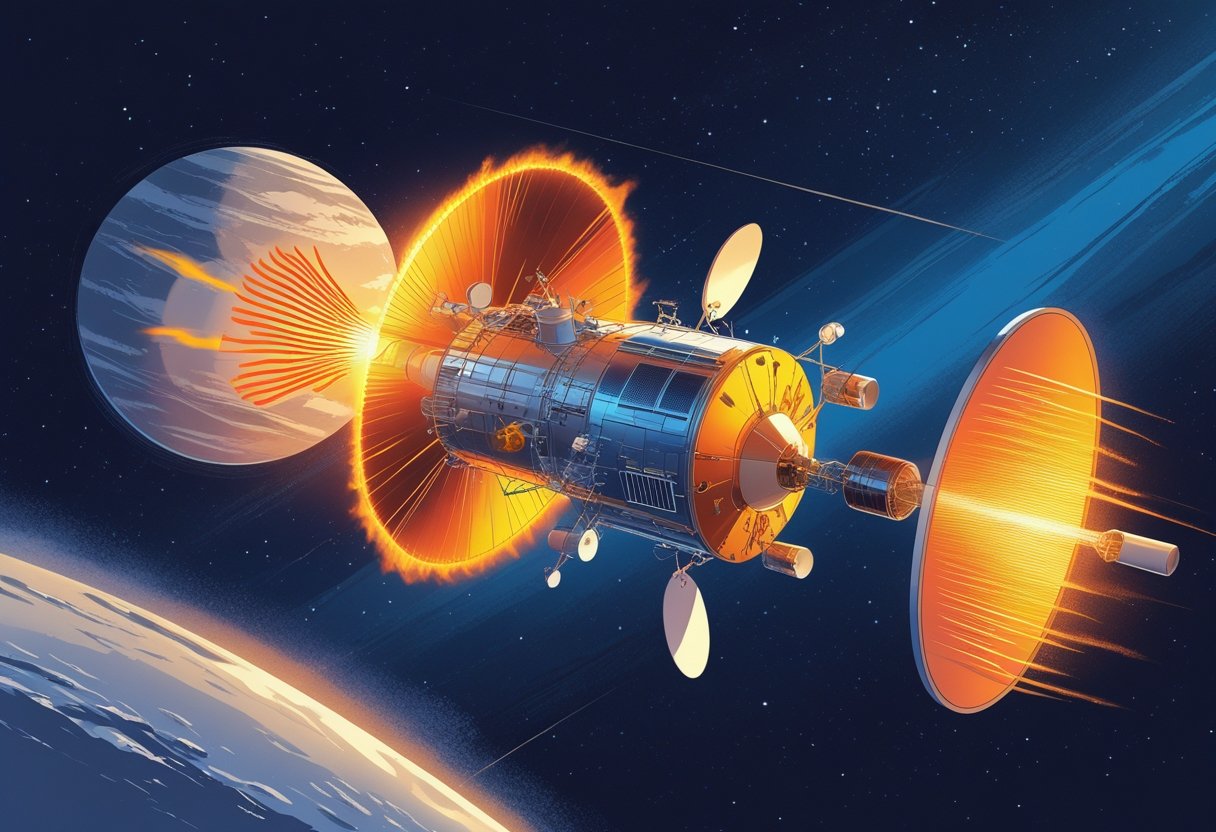

Active thermal control systems remove, transport, and regulate heat using powered devices and moving fluids. You’ll see radiators that dump heat to space, high-conductance heat pipes that move energy without pumps, fluid loops that carry kilowatts between sources and rejection panels, and point heaters or RHUs that maintain component survival temperatures.

Radiators and Deployable Technologies

Radiators provide the primary path for thermal rejection by emitting infrared radiation to deep space. You mount them on spacecraft faces with clear views to cold space and coat them with low-absorbance, high-emittance finishes to maximize radiative heat loss. Payload and avionics heat loads dictate radiator area; typical design trades balance area, mass, and attitude constraints.

Deployable radiators extend rejection area after launch to save stowed volume and mass. They use hinges, booms, or foldable panels and require reliable deployment mechanisms and thermal coupling to the spacecraft. You must account for joint thermal resistance, micro-meteoroid risk, and radiator orientation during maneuvers.

Key considerations:

- Emissivity and optical properties of coatings.

- Structural stiffness versus mass for large panels.

- Integration with fluid loop or thermal strap attachment points.

- Thermal control during eclipse or high-sun conditions.

Heat Pipes and Loop Heat Pipes

Heat pipes transport heat passively via phase change of a working fluid along a wick or capillary structure. You can use them to move tens to hundreds of watts across several meters with negligible temperature drop. Their reliability and zero-moving-parts operation make them ideal for distributing heat from electronics racks to radiators or colder structural members.

Loop Heat Pipes (LHPs) provide higher transport capacity and longer-distance routing using capillary-driven circulation in an evaporator, condenser, and compensation chamber. You’ll prefer LHPs when gravity-insensitive performance and handling of variable heat loads are required. LHPs tolerate bends and long runs better than conventional heat pipes but need careful priming and startup analysis.

Design points to watch:

- Working fluid selection for operating temperature range.

- Wick permeability and capillary limit vs. heat load.

- Thermal resistance of evaporator and condenser interfaces.

- Orientation sensitivity and startup conditions for mission profiles.

Thermoelectric Coolers and Fluid Loops

Thermoelectric coolers (TECs) use the Peltier effect for localized temperature control. You can place TECs on detector assemblies or small instruments that need tight setpoints. TECs are compact and electrically controllable but inefficient for large heat loads, producing heat that must be rejected by a radiator or secondary loop.

Fluid loops carry large heat loads over distances using pumped coolant (glycol, propylene, or ammonia for high power). An active fluid loop consists of pumps, accumulators, valves, heat exchangers, and a radiator interface. You’ll size the loop for peak heat, control flow to balance multi-plate loads, and incorporate redundancy for pump failures.

Implementation notes:

- Pump power, flow stability, and vibration coupling to structures.

- Freeze and overheat protection strategies for long-duration missions.

- Integration of TECs as local nodes on larger fluid networks.

- Monitoring and leak detection systems.

Radioisotope Heater Units (RHU) and Heaters

Radioisotope Heater Units provide continuous, long-duration warmth using decay heat from isotopes like plutonium-238. You rely on RHUs for survival heating of instruments and propulsion tanks in cold environments where electrical power is limited. Each RHU typically supplies a few watts of thermal power and requires containment, shielding, and careful placement.

Electrical resistance heaters and thermostatically controlled heaters give precise, on-demand power for components and plumbing. You’ll use them for de-icing, preventing coolant freeze, or maintaining battery temperature during eclipse. Heaters integrate with the ATCS via controllers and temperature sensors to prevent overheating.

Safety and operational factors:

- RHU placement relative to sensitive instruments and structure.

- Heater control logic for duty cycling and power budgeting.

- Redundancy and fail-safe design for survival heating.

- Compliance with launch and planetary protection regulations.

For additional background on active thermal control capabilities and architectures, review NASA’s discussion of thermal systems and testing facilities.

Advanced Thermal Management Innovations

You will learn current, high‑impact technologies that reduce mass, increase heat transfer control, and allow compact, high‑power electronics to operate reliably in space.

Additive Manufacturing and Novel Structures

You can use additive manufacturing to create complex heat paths and tailor thermal mass without heavy joins. Metal 3D printing (e.g., selective laser melting) lets you embed micro‑channels, graded porosity, and integrated heat pipes directly into structural panels. That reduces interface resistance and removes fasteners that add mass and thermal breaks.

Designs exploit lattice cores and biomimetic channels to increase surface area and encourage radiative cooling where conduction is limited. You should focus on print orientation, support removal, and post‑print heat treatment because those parameters control thermal conductivity and fatigue life. Qualification requires thermophysical testing, thermal cycling, and non‑destructive inspection to validate as‑built performance.

Phase Change Materials and Storage

Phase change materials (PCMs) absorb and release latent heat to smooth temperature swings during eclipse or peak power events. You can select paraffins for low‑mass, mid‑temperature buffering or salts for higher temperature pulses, depending on your component temperature limits.

Encapsulation is critical: micro‑encapsulation or containerized PCM prevents leakage and controls expansion. Integrate PCMs with heat pipes or conductive plates to move heat into the storage element quickly. When designing, calculate melt fraction, cycle life, and thermal resistance between the PCM and the structure so you meet mission duty cycles and avoid supercooling or phase segregation.

Thermal Switches and Straps

Thermal switches let you connect or disconnect thermal paths on demand to control when and where heat goes. Mechanical and cryogenic thermally actuated switches offer high on/off conductance ratios; gas‑gap switches provide variable control for lower mass systems. You should specify switching temperature, hysteresis, and steady‑state conductance to match mission phases.

Flexible thermal straps made from braided copper or pyrolytic graphite conduct heat while isolating vibration. Use straps to route waste heat from electronics racks to radiators without adding rigid mounts. Consider strap length, cross‑section, and interface termination: longer straps lower stiffness but increase thermal resistance, so balance mechanical and thermal requirements when sizing.

Thermal Interface Materials and Contact Conductance

Thermal interface materials (TIMs) bridge microscopic gaps between mating surfaces and dominate contact conductance in many assemblies. You can choose between gap fillers, phase‑change TIMs, metal foils, and compliant graphite layers based on required conductance, preload, and outgassing limits.

Maximize contact conductance by increasing contact pressure, improving surface flatness, and minimizing cured thickness for polymer TIMs. For high‑power joints prefer metal TIMs or indium foils to avoid creep and loss of contact at elevated temperatures. Validate TIM selection with vacuum thermal‑vacuum tests and joint‑level thermal cycling to ensure long‑term stability and acceptable mass for your spacecraft.

Special Cases: Surviving Re-Entry and Lunar Nights

Re-entry and lunar night force spacecraft systems to manage extreme heat and extreme cold at the same time. You need robust thermal protection, localized heating, and precise thermal control to protect crew, instruments, and avionics.

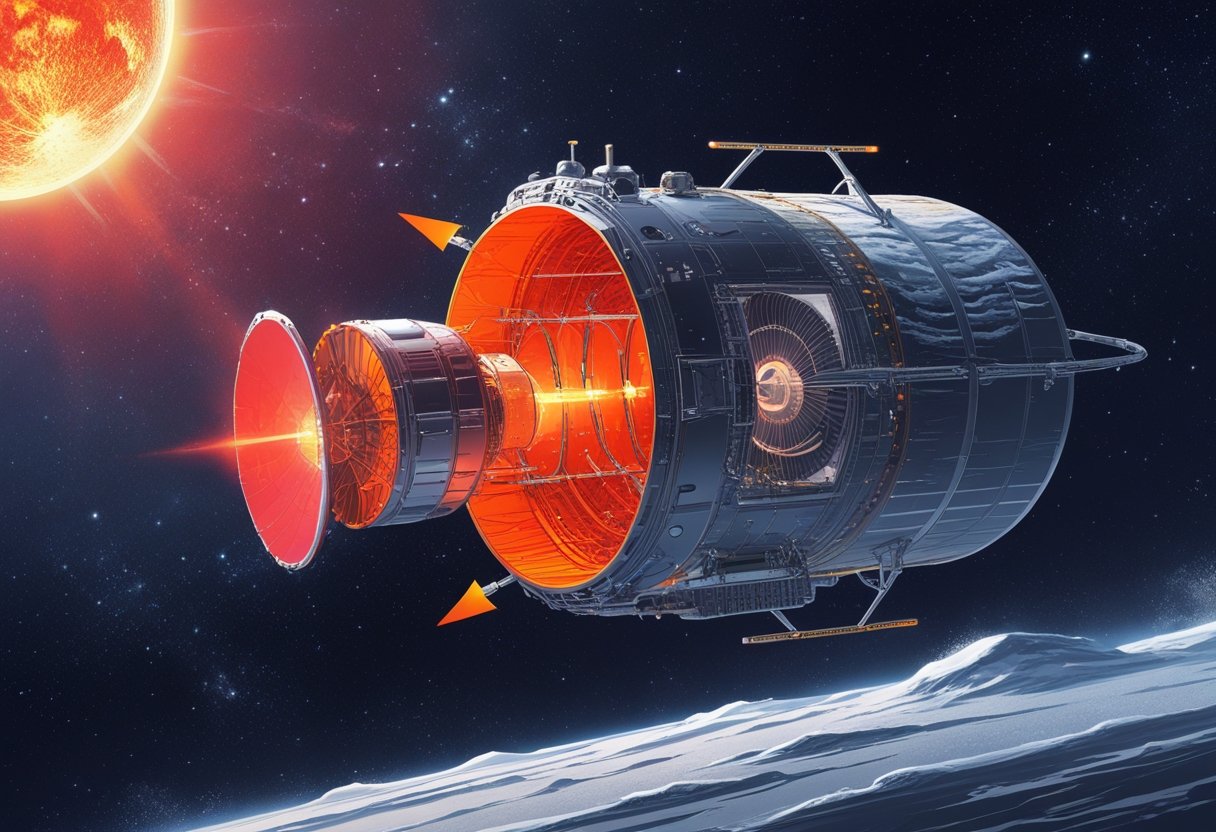

Thermal Protection During Atmospheric Re-Entry

During re-entry you face surface temperatures that can approach 1,600°C to 3,000°F (about 1,600°C). Heat loads concentrate on the vehicle’s leading edges and base. You rely on ablative or reusable heat shields that absorb and carry away energy by char, melt, and controlled erosion—materials sacrificially convert kinetic energy to manageable thermal and chemical byproducts.

Active cooling is rare on blunt-body capsules; instead, designers use shape and materials to generate a shock layer that keeps most heat in the plasma sheath. Thermal rejection during subsonic flight depends on conduction and radiation through insulators and structural layers. For winged vehicles, high-temperature ceramics, reinforced carbon–carbon, and advanced tiles provide localized protection where temperatures spike.

You must also protect internal systems: multilayer insulation, thermal doublers, and heat sinks route residual heat away from avionics and crew compartments. Precision thermal modeling and test campaigns validate that your heat shield, structure, and seals will survive both peak heating and rapid deceleration loads.

Spacesuit Thermal Regulation

Your spacesuit must keep you between roughly 18–27°C inside while the exterior can swing from −150°C to +120°C or more. The suit’s primary control is a liquid cooling and ventilation garment (LCVG) that pumps water through tubing to collect metabolic heat and transport it to a sublimator or radiator. The LCVG gives you fine control during EVA exertion and rest.

Insulative layers and reflective outer fabrics minimize radiative gain from sunlight and loss to shadowed space or lunar night. For lunar night survival you may need localized heaters or a radioisotope heater unit (RHU) to maintain critical electronics and battery temperatures. Your suit also integrates thermal sensors and closed-loop control so heating and cooling modulate with activity level and external conditions.

Mobility restrictions and mass constraints limit how much passive insulation you can add, so thermal design balances flexibility, power draw for active systems, and redundancy to protect you during long EVAs.

Maintaining Star Tracker and Instrument Performance

Star trackers and optical instruments require temperature stability within tight limits to preserve alignment and detector sensitivity. You must keep optics from warping or condensating while rejecting waste heat from nearby electronics. Use thermal isolation mounts, low-expansion materials, and localized heaters to maintain instrument temperatures within specified bands.

Active thermal management includes heat pipes and loop heat pipes to move heat to radiators or to controlled warm boxes during lunar night. A warm box approach preserves star trackers and avionics by isolating them with multilayer insulation and a controlled heater budget, reducing the chance of thermal drift that spoils pointing accuracy.

For missions near the Moon, design the thermal link so it can be cut or throttled during lunar night to retain heat, then re-enabled during daylight for thermal rejection. This lets your star trackers remain within operational limits despite external swings and ensures navigation and science data remain accurate.

Leave a Reply